High in the mountains of northern Colorado, a 100-foot tall

tower reaches up through the pinetops. Brightly coloured and strung with

garlands, its ornate gold leaf glints in the sun. With a shape that

symbolises a giant seated Buddha, this lofty stupa is intended to

inspire those on the path to enlightenment.

Visitors here to the

Shambhala Mountain Centre meditate in silence for up to 10 hours every

day, emulating the lifestyle that monks have chosen for centuries in

mountain refuges from India to Japan. But is it doing them any good? For

two three-month retreats held in 2007, this haven for the eastern

spiritual tradition opened its doors to western science. As attendees

pondered the "four immeasurables" of love, compassion, joy and

equanimity, a laboratory squeezed into the basement bristled with

scientific equipment from brain and heart monitors to video cameras and

centrifuges. The aim: to find out exactly what happens to people who

meditate.

After several years of number-crunching, data from the so-called

Shamatha project

is finally starting to be published. So far the research has shown some

not hugely surprising psychological and cognitive changes –

improvements in perception and wellbeing, for example. But one result in

particular has potentially stunning implications: that by protecting

caps called telomeres on the ends of our chromosomes,

meditation might help to delay the process of

ageing.

It's

the kind of claim more often associated with pseudoscience. Indeed,

since researchers first started studying meditation, with its close

links to religion and spirituality, they have had a tough time gaining

scientific credibility. "A great danger in the field is that many

researchers are also meditators, with a feeling about how powerful and

useful these practices are," says Charles Raison, who studies mind-body

interactions at Emory University in Atlanta. "There has been a tendency

for people to be attempting to prove what they already know."

But a

new generation of brain-imaging studies and robust clinical trials is

helping to change that. Scientists from a range of fields are starting

to compile evidence that rather than simply being a transient mental or

spiritual experience, meditation may have long-term implications for

physical health.

There are many kinds of meditation, including

transcendental meditation, in which you focus on a repetitive mantra,

and compassion meditation, which involves extending feelings of love and

kindness to fellow living beings. One of the most studied practices is

based on the Buddhist concept of mindfulness, or being aware of your own

thoughts and surroundings. Buddhists believe it alleviates suffering by

making you less caught up in everyday stresses – helping you to

appreciate the present instead of continually worrying about the past

or planning for the future.

"You pay attention to your own

breath," explains Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist who studies the effects

of meditation at Massachusetts general hospital in Boston. "If your mind

wanders, you don't get discouraged, you notice the thought and think,

'OK'."

Small trials have suggested that such meditation creates

more than spiritual calm. Reported physical effects include lowering

blood pressure, helping psoriasis to heal, and boosting the immune

response in vaccine recipients and cancer patients. In a pilot study in

2008, Willem Kuyken, head of the Mood Disorders Centre at Exeter

University, showed that mindfulness meditation was more effective than

drug treatment

in preventing relapse in patients with recurrent depression. And in 2009, David Creswell of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh found that it

slowed disease progression in patients with HIV.

Most

of these trials have involved short courses of meditation aimed at

treating specific conditions. The Shamatha project, by contrast, is an

attempt to see what a longer, more intensive course of meditation might

do for healthy people. The project was co-ordinated by neuroscientist

Clifford Saron of the Centre for Mind and Brain at the University of

California, Davis. His team advertised in Buddhist publications for

people willing to spend three months in an intensive meditation retreat,

and chose 60 participants. Half of them attended in the spring of 2007,

while the other half acted as a control group before heading off for

their own retreat in the autumn.

It sounds simple enough, but the

project has taken eight years to organise and is likely to end up

costing around $4m (partly funded by private organisations with an

interest in meditation, including the Fetzer Institute and the Hershey

Family Foundation). As well as shipping laptops all over the world to

carry out cognitive tests on the volunteers before the study started,

Saron's team built a hi-tech lab in a dorm room beneath the Shambhala

centre's main hall, enabling them to subject participants and controls

to tests at the beginning, middle and end of each retreat, and worked

with "a village" of consulting scientists who each wanted to study

different aspects of the meditators' performance. "It's a heroic

effort," says neuroscientist Giuseppe Pagnoni, who studies meditation at

the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy.

Many of the

tests focused on changes in cognitive ability or regulation of emotions.

Soft white caps trailing wires and electrodes measured the meditators'

brain waves as they completed gruelling computerised tasks to test their

powers of attention, and video recordings captured split-second changes

in facial expressions as they watched images of suffering and war.

But

psychologist Elissa Epel, from the University of California, San

Francisco (UCSF), wanted to know what the retreat was doing to the

participants' chromosomes, in particular their telomeres. Telomeres play

a key role in the ageing of cells, acting like a clock that limits

their lifespan. Every time a cell divides, its telomeres get shorter,

unless an enzyme called telomerase builds them back up. When telomeres

get too short, a cell can no longer replicate, and ultimately dies.

It's

not just an abstract concept. People with shorter telomeres are at

greater risk of heart disease, diabetes, obesity, depression and

degenerative diseases such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. And they

die younger.

Epel has been collaborating with UCSF's Elizabeth

Blackburn, who shared the 2009 Nobel physiology or medicine prize for

her work on telomeres, to investigate whether telomeres are affected by

psychological factors. They found that at the end of the retreat,

meditators had

significantly higher telomerase activity

than the control group, suggesting that their telomeres were better

protected. The researchers are cautious, but say that in theory this

might slow or even reverse cellular ageing. "If the increase in

telomerase is sustained long enough," says Epel, "it's logical to infer

that this group would develop more stable and possibly longer

telomeres over time."

Pagnoni has previously used brain imaging to show that meditation may

protect against the cognitive decline

that occurs as we age. But the Shamatha project is the first to suggest

that meditation plays a role in cellular ageing. If that link is

confirmed, he says, "that would be groundbreaking".

So how could

focusing on your thoughts have such impressive physical effects? The

assumption that meditation simply induces a state of relaxation is "dead

wrong", says Raison. Brain-imaging studies suggest that it triggers

active processes within the brain, and can cause physical changes to the

structure of regions involved in learning, memory, emotion regulation

and cognitive processing.

The question of how the immaterial mind

affects the material body remains a thorny philosophical problem, but on

a practical level, "our understanding of the brain-body dialogue has

made jaw-dropping advances in the last decade or two," says Raison. One

of the most dramatic links between the mind and health is the

physiological pathways that have evolved to respond to stress, and these

can explain much about how meditation works.

When the brain

detects a threat in our environment, it sends signals to spur the body

into action. One example is the "fight or flight" response of the

nervous system. When you sense danger, your heart beats faster, you

breathe more rapidly, and your pupils dilate. Digestion slows, and fat

and glucose are released into the bloodstream to fuel your next move.

Another stress response pathway triggers a branch of the immune system

known as the inflammatory response.

These responses might help us

to run from a mammoth or fight off infection, but they also damage body

tissues. In the past, the trade-off for short bursts of stress would

have been worthwhile. But in the modern world, these ancient pathways

are continually triggered by long-term threats for which they aren't any

use, such as debt, work pressures or low social status. "Psychological

stress activates these pathways in exactly the same way that infection

does," says Raison.

Such chronic stress has devastating effects,

putting us at greater risk of a host of diseases including diabetes,

cancer, heart disease, depression – and death. It also affects our

telomeres. Epel, Blackburn and their colleagues found in 2004 that

stressed mothers caring for a chronically ill child

had shorter telomeres than mothers with healthy children. Their stress had accelerated the ageing process.

Meditation

seems to be effective in changing the way that we respond to external

events. After short courses of mindfulness meditation, people produce

less of the stress hormone cortisol, and mount a smaller inflammatory

response to stress. One study linked meditators' lower stress to changes

in the amygdala – a brain area involved in fear and the response to

threat.

Some researchers think this is the whole story, because

the diseases countered most by meditation are those in which stress

plays a major role. But Epel believes that meditation might also trigger

"pathways of restoration and enhancement", perhaps boosting the

parasympathetic nervous system, which works in opposition to the fight

or flight response, or triggering the production of growth hormone.

In

terms of the psychological mechanisms involved, Raison thinks that

meditation allows people to experience the world as less threatening.

"You reinterpret the world as less dangerous, so you don't get as much

of a stress reaction," he says. Compassion meditation, for example, may

help us to view the world in a more socially connected way. Mindfulness

might help people to distance themselves from negative or stressful

thoughts.

The Shamatha project used a mix of mindfulness and

compassion meditation. The researchers concluded that the meditation

affected telomerase by changing the participants' psychological state,

which they assessed using questionnaires. Three factors in particular

predicted higher telomerase activity at the end of the retreat:

increased sense of control (over circumstances or daily life); increased

sense of purpose in life; and lower neuroticism (being tense, moody and

anxious). The more these improved, the greater the effect on the

meditators' telomerase.

For those of us who don't have time for

retreats, Epel suggests "mini-meditations" – focusing on breathing or

being aware of our surroundings – at regular points throughout the day.

And though meditation seems to be a particularly effective route to

reducing stress and protecting telomeres, it's not the only one. "Lots

of people have no interest in meditation, and that's fine," says

Creswell. Exercise has been shown to buffer the effects of stress on

telomeres, for example, while stress management programmes and writing

emotional diaries can help to delay the progression of HIV.

Indeed,

Clifford Saron argues that the psychological changes caused by the

Shamatha retreat – increased sense of control and purpose in life – are

more important than the meditation itself. Simply doing something we

love, whether meditating or gardening, may protect us from stress and

maybe even help us to live longer. "The news from this paper is the

profound impact of having the opportunity to live your life in a way

that you find meaningful."

For a scientific conclusion it sounds

scarily spiritual. But researchers warn that in our modern,

work-obsessed society we are increasingly living on autopilot, reacting

blindly to tweets and emails instead of taking the time to think about

what really matters. If we don't give our minds a break from that

treadmill, the physical effects can be scarily real.

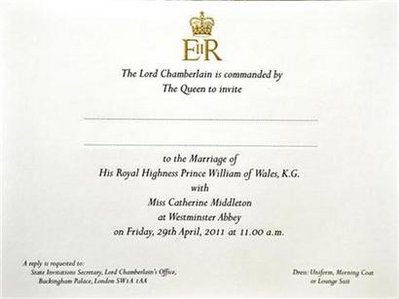

Whether you will

be watching every moment or just want to see the ceremony, Yahoo! will

be your one stop for all royal

wedding updates. You won't miss a thing. Here's what you can

expect:

Whether you will

be watching every moment or just want to see the ceremony, Yahoo! will

be your one stop for all royal

wedding updates. You won't miss a thing. Here's what you can

expect:

final at Wembley after second-half goals from Giggs and

final at Wembley after second-half goals from Giggs and